Calypso, Trinbagonian English, and Creole Ambivalence

Jocko MacNelly

Hamline University

Submitted to:

Professor Kathryn Heinze

ESL 7519: Linguistics for

Language Teachers

Spring 2007

To appreciate calypso music is to appreciate the insight, wit and, sooner or later, the language of its creators. The singer-composers working in this genre typically comment on a stunning variety of topics ranging from the universal to the parochial. The best calypsos are delivered with humor (sometimes a black humor indeed) and a love of the language, or languages, which make up the Trinidadian linguistic heritage. As such, the literature of Calypso can serve as a useful point of departure for a forrenuh wishing to investigate this language. What then, are the characteristics of the language spoken (and sung) by the musical reporters, commentators, satirists, entertainers, griots, and poets responsible for this rich literature? This paper will represent an attempt to begin answering that question, or at least to identify some issues involved in arriving at a broad description of the language. I will set down some of the ways in which Trinbagonian English (which, for all its variety, will simply be referred to using the umbrella designation TE) is an expression of the multicultural environment of its home, and will note and try to account for occurances of variation in phonology, morphology, vocabulary and register.

A Sociolinguistic Overview of Trinbagonian English

French, Spanish and English

According to a Trinidadian informant who makes frequent visits back home, Spanish is coming into greater use in present day Trinidad, due to geography, tourism and the reach of the media. However, three centuries of Spanish occupation (beginning in 1498) did not leave a proportionately deep linguistic imprint. There was little opportunity available for the survival and development of whatever means of communicatrion exsisted between slaves and their overseers. The island’s population never exceeded 1,400 persons, there was a high mortality rate throughout the Caribbean among all levels of society, and it was seen to be more economical to replace and augment the workforce through the importation of new slaves rather than by breeding.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, the population of Trinidad spiked as turmoil in the French-speaking world, notably the French and Haitian revolutions, precipitated a wave of French immigration to the island, beginning officially in 1783. By the time of the British takeover in 1797, what had been a Spanish outpost was now a French colony in all but name and government. Official business was conducted in Spanish but otherwise, French had become the language of business and status. Significantly, out of a population that had ballooned to 28,000, an estimated 20,000 were French creole-speaking African slaves (Ferreira, p2). Language policy under the British reflected the general state of political conflict between the British and the French at the time, and the introduction, official use, and domination of English (at the expense of French) became a matter of political policy for the island’s new rulers. The old language, known as patois proved durable, but has been in decline since the early 20th century. According to one informant, a white Trinidad native in his mid-fifties, “As a language patois is not common except amongst the older generation (my mother’s age) and up.” The lexicon retains hundreds of patois words and sayings, however, among them: crapaud toad (which gives us the descriptive creole-patois combination mash-crapaud, meaning roadkill), mauvais lang to gossip, Ti Marie, a native plant with sensitive leaves and many thorns, pagnol (/pajøl/) someone of obvious Spanish descent, doux-doux a term of endearment, and bazodee distracted, as in she have me bazodee. There is also the calque “it have,” for il y a, as in “it only have few people sheltering rain on the pavement (Selvon, in Livingston, p. 87).”

The status of patois has changed as its use has diminished. In a bit of stage business clearly meant to be basilectal, a woman informs Lord Kitchener/ai k¨d wain tu uno/ I can wind too, you know (Dutta, 1988). The /u/ in /uno/ is a holdover from the former status language, being the second person singular pronoun, which is spelled ou or w in Haitian Kreyol. While patois is the accepted term for the survivng French dialect in Trinidad, the term “French Creole” is used, sometimes derogatorily, to describe whites in general. Trinidadians, of necessity, are not fussy about ethnic distinctions. Anyone of Middle-eastern descent for instance, “no matter if Turkish, Arab, or Egyptian” (according to my informant), is referred to as “Syrian.”

Continuing Societal and Linguistic Stratification

Later waves of immigration brought other ethnic groups which are now a conspicuous part of Trinidadian society. Even into the twentieth century however, a certain stratification remained in place. V.S. Naipaul, in his short story “The Baker’s Story” describes a mid-twentieth century Trinidad in which different ethnic groups interact comfortably, yet, by general agreement, keep to themselves in certain matters. In Naipaul’s story, a black Grenadian opens a bakery in a small town outside of Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, and is entirely unable to lure customers, until he hits upon a fundamental aspect of Trinidadian culture:

And then I see that though Trinidad have every race and every color, every race have to do special things....If you want to buy a snowball, who you buying it from? You wouldn’t buy it from a Indian or a Chinee or a Potogee. You would buy it from a black man....Who ever see a Indian carpenter?.....If a black man open a laundry, you would take your clothes to it? I wouldn’t take my clothes there. (Livingston, p.126)

Trinidadians, then, live in a rich multicultural and multidialectical environment in which they appear to be conscious, even enthusiastic, participants, switching registers, accents and dialects with ease. This is something which is seen as normal in the West Indies in general (Roberts, 1988), and in Trinidad proper, children as young as two have been shown to be able learn competent and appropriate code-mixing (Youssef, 2004).

Status and Register

Status, Africa and Europe

Dah language weh yuh proud a

Weh yuh honour an respec-

Po Mas Charlie, yuh no know se

Dat it spring from dialec! (Louise Bennett, quoted in Morris, 1993, p.20)

“A dat yuh modder sen yu a school fa?” (Morris, 1993, p.22)

In such a mixed cultural and linguistic environment as Trinidad’s, it should come as no surprise that there is a mixture of attitudes toward language use among the inhabitants as well. This is also true for the greater Caribbean, and cuts across issues as broad as the conflict between regional versus national identification, or as personal as local accent and register. The first quote at the beginning of this section is from the poem “Bans a Killin” by Jamaican poet and actress Louise Bennett, which is addressed to someone (“Po Mas Charlie”) who wants to promote “good” (that is to say, standard) English, and do away with Jamaican patois. The second is a disapproving comment Bennett herself recalled receiving at a reading of her dialect verse.

On one hand, there is a psychological need on the part of former colonial subjects to assert their own cultural and linguistic identity, to speak “we own language.” On the other, there are centuries of conditioning that need to be undone for the new nations’ own identity to find full expression. It seems reasonable to expect that the language of, to be blunt, “the people with the money,” be seen as a target language, as “good” English. Smitherman sees the conflict as essentially being between two broadly different attitudes towards language. One culture, the European, places a high value on writing, reading, and the printed word. The other, brought from Africa on the slave ships, reveres the power of the spoken word (1977, also see Roberts, 1988), and accords status to displays of verbal agility. One (the European) point of view could be said to value the tangible preservation of knowledge, while in the other there is a more immediate relationship to it. There is equal interest in the preservation and transmission of culture and information on the part of both traditions, but it is in the nature of the preservation and transmission that we encounter differences. According to Morris, in the West Indian mind, Creole is “the language of feeling, their most intimate language,” and is associated with speech, while higher status variety is associated with print, books, education (1993, p.23). The crux of the issue, embodied in the question posed by Louise Bennett’s heckler, is that one may aspire to both intimacy and erudition.

The close relationship of message and the quality of its delivery informs the literature of Calypso as well. In the documentary film “One Hand Don’t Clap,” Lord Kitchener (Aldwyn Roberts, 1922-2000, the subject of the film) is reminiscing with another old Calypsonian, Lord Pretender, who is decrying the displacement of traditional Calypso by Soca (“soul-calypso”), a less lyric-oriented form:

LP: Nowaday dey ain rhymin, lyrics, anyhow. An de music singin f’dem, mostly i’ de music. A man sing a line, de music play five minutes.

LK: Dat de soca. A stronger beat, wid less lyrics.

LP: I...I kan ‘nderstand it ‘tall. (I can’t understand it at all) (1988)

Register

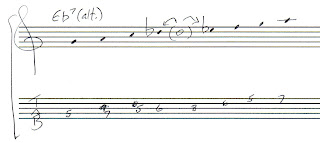

Along with lexical morphological and phonological cues we might use to separate the different registers of Trinidadian speech, we can even use musicological cues. This is of course not a musicology paper, but the insight it gives as to the consciousness of registers and their relative cultural placement in Trinidad is so compelling that it merits at least a brief mention here. Consider two songs by Lord Kitchener, “Tie-tongue Mopsy,” and “Trouble in Arima.” Musically, the former is typical of tune by “Kitch,” featuring a complex, harmonically aware melody and a sophisticated harmonic vocabulary. The lyrics tell of a romantic encounter between the narrator and a young woman with a speech impediment. Kitch uses the contrast between his impersonation of the girl’s garbled speech in the chorus and his high-flown rhetoric in the verses, which is known in the West Indies as “talking sweet” (Roberts, 1988), to comic effect.

I spoke a very English word that reach my memory,

Just to apprehend her sympathy

I said ‘dear, you know I would not dissemble

My love to you is inexpressible’

He is even uncharacteristically prim about sex: “In the midst of romance I coolly stole a kiss/ And then I request a little stupidness.”

In stark musical and linguistic contrast is “Trouble in Arima” which Kitch delivers in a nasalized tone throughout perhaps as parody, perhaps to put some distance between his normal stage persona and the character he is portraying in the song.

(Is trouble) I am waiting (Is trouble), rong de corner

(Is trouble) Ahh, wid me cutlass (Is trouble), for dem terror

Here, the basilect is used to convey an agressive text, and is reflected in the uncharacteristic simplicity of Kitch’s music. This melody is based entirely on a recurring two-measure phrase, with only two chords alternating throughout. Lyrically, Kitch abandons his usual articulate style to deliver lines of (usually) four syllables, using mostly one-syllable words. Also, while African-style call and response is present in calypso music, it is rarely, as it here, the main structural element of the song. Kitch consciously brings the music with him to the basilectal end of the continuum.

Code-mixing and Features of TE

Part of the Trinidadian’s linguistic competence involves code-mixing bi-directionally along the continuum (Youssef, 2004). This ability may be said to be an important feature of TE in and of itself, and any investigation of liguistic features of the dialects spoken in Trinidad should take this into account. Youssef states that the switching is systematic (2004) though it is unclear whether she means this in terms of longer texts or of isolated segments. This propensity for code-switching on the part of Trinbagonians does lend a veneer of unpredictability to descriptions of what are considered “normal” aspects of Caribbean speech habits. Certain features, to be sure, are predictable, such as syllable-timing (Roberts, 1988) and the characteristics of accent and tone which may arise from this. For example, a Trinidadian d.j. can be heard on Youtube.com (“Trini talk”) to say /g´ tw´nti d√l√z æn g´ta dis´n roti/. We can also count on this absence of flaps, so that SE [扫øl] at all, becomes, in TE, [æ«tøl] (as in Pretender’s complaint, above). Entirely predictable is the sound /æwn/ as in town being expressed as /ø˜/. So Lord Kitchener is perfectly comfortable using the rhyming couplet /nø ai bak în tø˜, ai go si dæt n√tˆn go rø˜/ now (that) I(’m) back in town, I go see that nuttin go wrong (Law and Order).

But many syntactical, lexical, morphological, and phonological features are best viewed as having been chosen from a range of options available to the TE speaker. The way in which these choices are arrived at systematically is no doubt a fascinating study

Lexical Variation

In a serious but casual conversation about calypso music between four men in a restaurant, the singer Black Stalin switches seemingly at random between the use of the word calypso, and its more creole-ized form [«kayso], using [cal«îpso] and [«kayso] three times each within forty seconds. At the beginning of the scene Stalin is already talking: “....you kya jus have calypso fuh one pa’ticular time.” But seconds later he asks: “What is kaiso?” /w√«tˆz «kayso/ (Dutta, 1988). It seems as though, in every instance, [«kaiso] is directly preceded by a word or segment that could be considered a creolism.

Syntactical and Morphological Variation

Earlier in the film we see Calypso Rose at work composing a song to be called “Terrorism Gone Wild.” Rose is sitting at a desk, presumably in her home, with a candle, a drink, her guitar, pen, paper, and a cassette recorder. As the scene begins, Rose is pondering a line, murmuring to herself and writing. The monologue is telling: “From doze. From doze fanatics. (she sings a couple of notes) From de- (d´), from doze. From dem. We done, OK” (1988). There are also a couple of shots from behind Rose, so we can see over her shoulder and, pausing the playback, are able to read what she is writing, which affords a glimpse of her perception of her own language. She writes in a legible cursive, using standard spelling. On her lyric sheet, syntax and morphology are rendered in exactly the way she is later heard to sing it in a recording session: “Is kidnapping bombs and gun, terrorist have me on the run.” Her use of is and have is regular. Plurals in the Caribbean are mostly uninflected, though sometimes followed by a plural marker, as in the Jamaican di pickny-dem, the children. Dem may just sound better to the composer than doze; the uninflected plural gun may rhyme better with run. But what is interesting about Rose’s lyric sheet, and her musings about dem and dose, is the way in which there are clear-cut morphological choices of more or less equal value, which are then intentionally applied.

Phonological Variation

Besides the rendering of interdental fricatives as /d/ or /t/, another universally accepted feature of Caribbean English, and TE specifically, is palatalization after stops. Velar stops are usually cited as examples, though it can also be found in environments where SE speakers would normally affricate; perhaps this is due to syllable-timing. Once, during a discussion of an unpleasant professional situation thirty years ago, a Trinidadian colleague was heard to ask rhetorically “weh de fyuteah in dis?” /we di fjutj√ ˆn dˆs/. And in the film, Kitch says “Calypso is a recognize culteah” with the last word rendered as /k√ltj√/. Roberts states that palatalization is noteworthy in the Caribbean because it occurs more often than in other dialects (1988), but in Trinidad again, there are baffling examples of omission. Kitch, for instance, may refer to another calypso singer as /dj´vîd r√‰û/ David Rudder, and flirt with a female fan named Cynthia by saying “I have a girlfrien’ (/gjîlfr´n/) by d’name of Cynt’ia,” But in an interview he also says “but he cahnt get wid it. Cahnt get into it” (all from Dutta, 1988) where one normally expects /kja/ or/kjan/ (Confusion is avoided in TE by using /k¨d/ for the positive can ). This usage appears to be entirely unpredictable. In his lyrics, Kitch uses palatalized and unpalatalized forms interchangeably, so that, in the song “Pan in A-minor” he sings, in the first line, of “a musical change (/tßj´ndΩ/) in pan” and a few of lines later: “I decide to change (/tßendΩ/) to de minor chord” both on the original recording and in the live performance captured in “One Hand Don’t Clap.”

Conclusion

Trying to separate and classify the different levels of Trinidadian speech, as it is used by its overwhelmingly mulitdialectical population, may muddy the issue, or place distinctions where they don’t actually exsist. It seems as though, for “Trinis” to whom the full range of the island’s culture is available, it is not their language as a whole which occupies one place or the other on the creole continuum, but rather individual features. Syntax, morphology, phonological features, and vocabulary from any point in this spectrum may be drawn on at any time. This is an overarching feature of the language, and the one through which all the others need to be viewed.